[This is Part 4 in a series about my new book. Check out the previous installments here.]

Although I struggled for a long time—even after I’d written over 100 pages—with where in the story the reader’s experience should begin, eventually I settled on a spot that felt right to me. Without giving too much away, I wanted to show my main character in her natural environment, practicing law in New York City. This notion is derived from “Quest” literature in which the hero is first seen at home before setting off in search of some goal. This is the “world of common day” (to use Joseph Campbell’s term from The Hero with a Thousand Faces) or the “ordinary world” (to use Christopher Vogler’s application of Campbell’s analysis to mythic structures for writers in The Writer’s Journey). Glimpsing the hero in her ordinary world puts into context the adventure that she’s about to go on and gives the reader an idea of what’s at stake for her. That’s the theory, anyway.

So, the book begins in New York in the main character’s ordinary world, but before long she finds herself in Singapore. As I’ve described earlier in this series, when she gets there, she becomes aware of a woman who, many years earlier, came to Singapore and painted what she saw. My next challenge in the writing of the book was how to tell that woman’s story, too.

Early on, I opted to do this through diary entries. It seemed like a clear way to distinguish between the more contemporary narrative and the historical elements. For one thing, the diary entries are dated, so the reader should learn quickly that these chapters, which are generally shorter, are different from the other chapters. Also, the diary is in first person, naturally, whereas the contemporary part of the narrative is in third person. Finally, the language of the diary is different, more Victorian in prose style than the contemporary story.

The challenge for me was to figure out how to intersperse the diary entries with the narrative. In general, I tried to make the entries correspond in some way to what was happening in the main story, so that in addition to having its own narrative arc the diary would shed light on something that the main character is doing in the contemporary plot.

The logic of presenting the diary entries was also a puzzle for a long time. Why are the entries distributed throughout the book instead of appearing all together as a diary would be? And what does the main character do with the information in the diary? When I finally settled on answers to these questions, I finally felt comfortable with the weaving of the two stories together.

Probably you have read other novels that do this in some form. Before I got very far into the writing of the book, I asked on social media for examples of books that do this, and I was alerted to countless titles, many of which I then read. A frequent recommendation was A. S. Byatt’s Possession. Another was The Hours by Michael Cunningham. And then as I was finishing the book, Geraldine Brooks’s novel Horse came out. It was perhaps the best comparison of all because it involves a painting done more than a century before the contemporary narrative. Of course, by that time, my structure was settled, but the book, which has been widely read recently, is a useful way to explain my own novel’s form.

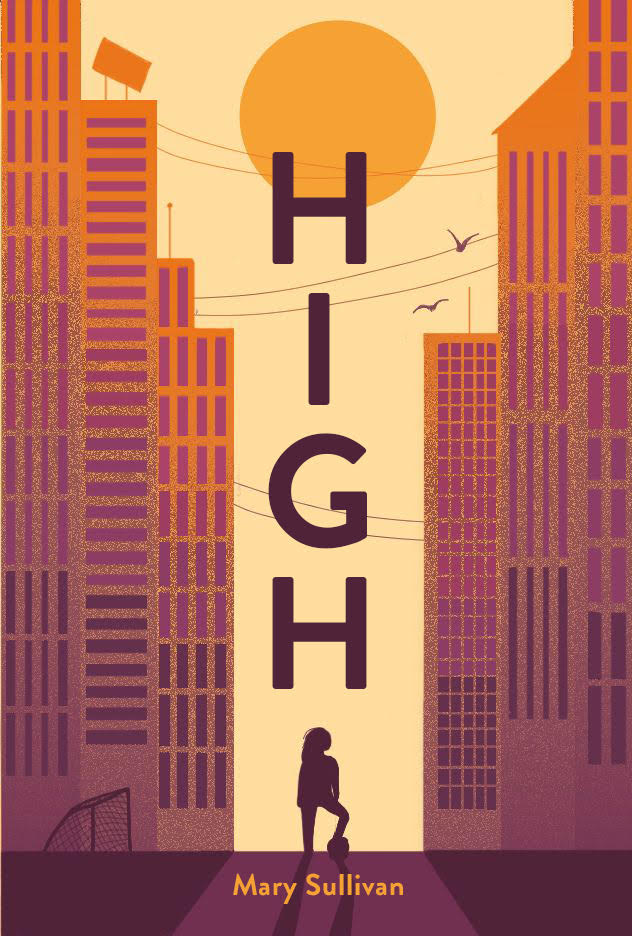

In case you were wondering where this series is going, eventually I’ll be telling you more about the plot, revealing the cover, and inviting you to pre-order the novel, which is often critical to the success of a book.

Next: The Agony of Traditional Publishing