Morningside Heights by Joshua Henkin is an odd sort of novel, mostly because there’s almost nothing odd about it. I kept looking for the novel’s raison d’etre, but I never settled on what it might be. It’s a domestic story about Pru and Spence who meet when Pru is his graduate student at Columbia in the 1970s. She has arrived from Columbus, Ohio, is somewhat naïve and infatuated. They begin sleeping together—a dangerous thing for a professor to do even back then, but the story, thankfully, doesn’t go there. Instead, Pru quits the program, they get married, and life goes on. It turns out, however, that Spence has a son from a short-lived previous marriage, and Arlo complicates things, but only just a little. In contrast with Spence, Arlo is no scholar and struggles in school. Then, along comes Sarah, Pru and Spence’s own daughter, and she is a stronger student. Arlo, too, eventually displays his more unconventional brilliance. But we learn fairly early in the book because of its jumbled timeline that Spence develops Alzheimer’s, and this is the challenge they all face. Frankly, there’s nothing very surprising in the story, which is unfortunate, because it’s otherwise a well-written book. My full review is in the New York Journal of Books.

The Anthropocene Reviewed by John Green is a collection of essays that allow Green to exercise his apparently boundless curiosity about . . . anything. In this case, there’s a bit of science and a bit of history strung together in these relatively short essays, giving the reader enough to chew on without being too much to absorb. Green is known for his excellent young adult novels, so this is a departure for him, but it’s one of the most enjoyable essay collections I’ve read. Being a subscriber to his YouTube channel, I saw him sign 250,000 insert pages for this book, which came out on the same day my latest novel was published, and the copy I bought includes one of those pages. The conceit of the book is that Green first writes about the origin of a star-rating system and then proceeds to apply the system to a variety of things that have drawn his attention—Halley’s Comet, Diet Dr. Pepper, Sunsets, etc.—in essays that are invariably charming. Each one reveals a tidbit of information about Green I didn’t know before (not that I knew much, but I have been aware of him for over a decade), such as that he’s a regular attendee at the Indy 500. Green is primarily a writer of YA novels, but I’ve read and appreciated his two most recent titles, The Fault in Our Stars and Turtles All the Way Down. One additional note: at a dinner in Indianapolis a few years ago honoring past winners of the various literary prizes awarded over the previous decade by the Indiana Authors Award (sponsored by the Eugene and Marylin Glick Foundation), Green and I were seated a few tables away. (He had won the National Author Award in 2012 and I had won the Emerging Author Award in 2015.) When dinner was over, my sister, who was with me, urged me to get Green’s autograph for her granddaughter, a big fan. I don’t ever do this, but I took the program for the evening, approached him, explained both that I was also a former award-winner and that my great-niece was a fan, and he graciously signed. So that was nice.

Homeland Elegies by Ayad Akhtar is a beautifully written puzzle and my book club’s selection for this month. Is it fiction? Is it memoir? While many of the details do seem to be drawn from Akhtar’s life, others may be fabricated. It’s impossible for the casual reader to know, and so I prefer to believe the book, which is called a novel, is fiction. It tells a story that is certainly close to Akhtar’s: a couple immigrate to the US from Pakistan to practice medicine—the husband is a cardiologist—and Ayad is born here. Time passes, he is heavily influenced by a brilliant college professor and becomes a writer. One of his plays wins the Pulitzer Prize (I saw that play, Disgraced, in a production in Washington DC), and he attracts a great deal of attention because he is Muslim, but his message is somewhat difficult to decipher, both for Muslims and non-Muslims. Meanwhile, things are happening around him, including a growing mistrust of Muslims, especially after 9/11. His mother dies, his father has a drinking and gambling problem, and is, supposedly, a Trump supporter (at least initially). And so on. It’s surprisingly gripping.

Life After Life by Kate Atkinson is the first of her Todd Family novels, and somehow I managed to read the second one first, but I remember loving that one (A God in Ruins) so apparently the order doesn’t matter. This book, which begins in 1910 with the birth of Ursula Todd, jumps around in time—ahead to much later events and then back to 1910, then forward again to alternative versions of events. At birth, Ursula seemed fated to die because of the umbilical cord wrapped around her neck, but as the scene is retold, the doctor (or in one version, the mother) is able to cut the cord and save her. Similar events transpire throughout her life, and she seems to have a vague notion of her death, or the death of others, or impending doom, and can take action to change the outcome. For example, in 1918, just as the end of the Great War is being celebrated, the family maid brings the Spanish Flu into the house and the disease kills Ursula’s beloved younger brother Teddy. Given a chance to relive the day, Ursula pushes the maid down the stairs, keeping her from going up to London to the celebration. The maid’s beau goes without her, contracts the flu, and dies, but in this version of events Teddy is saved. For now. More twists and turns follow. Fascinating book. (A God in Ruins, which focused on Teddy, had a similar alternative reality twist to it.)

The Light on Sifnos by Barbara Quick is a lovely chapbook of poems the author wrote on a Greek island while reading The Odyssey. The title poem begins “How does one describe the light here in this place/ where the dawn really does have rosy fingers,/ where the mountains glow at night,/ their barren slopes a magnet/ for the radiance of moon and stars.” Quick has written a number of novels, but I think this is her first collection of poetry.

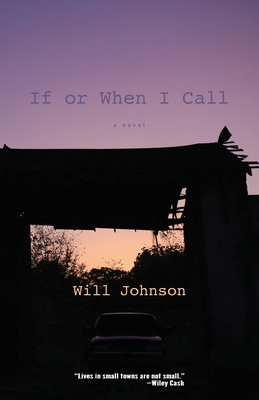

If or When I Call by Will Johnson is a gritty novel about hardscrabble, small-town life in Missouri. Parker and Melinda meet in a bar, marry, have a son, and then the marriage falls apart, partly because of Parker’s drinking and partly because of his “fits” which doctors can’t explain or control. They split up, and Parker does his best to be a good father to Ben, but Melinda’s life is going nowhere. Melinda’s generous sister encourages her to take a road trip, and in the process, she seems to come to an understanding of what she wants. Parker, meanwhile, solidifies his relationship with Ben, and a crisis seems to bring them all closer together. Apart from a couple of significant loose threads, it’s a readable story. My full review will appear in the Southern Review of Books.