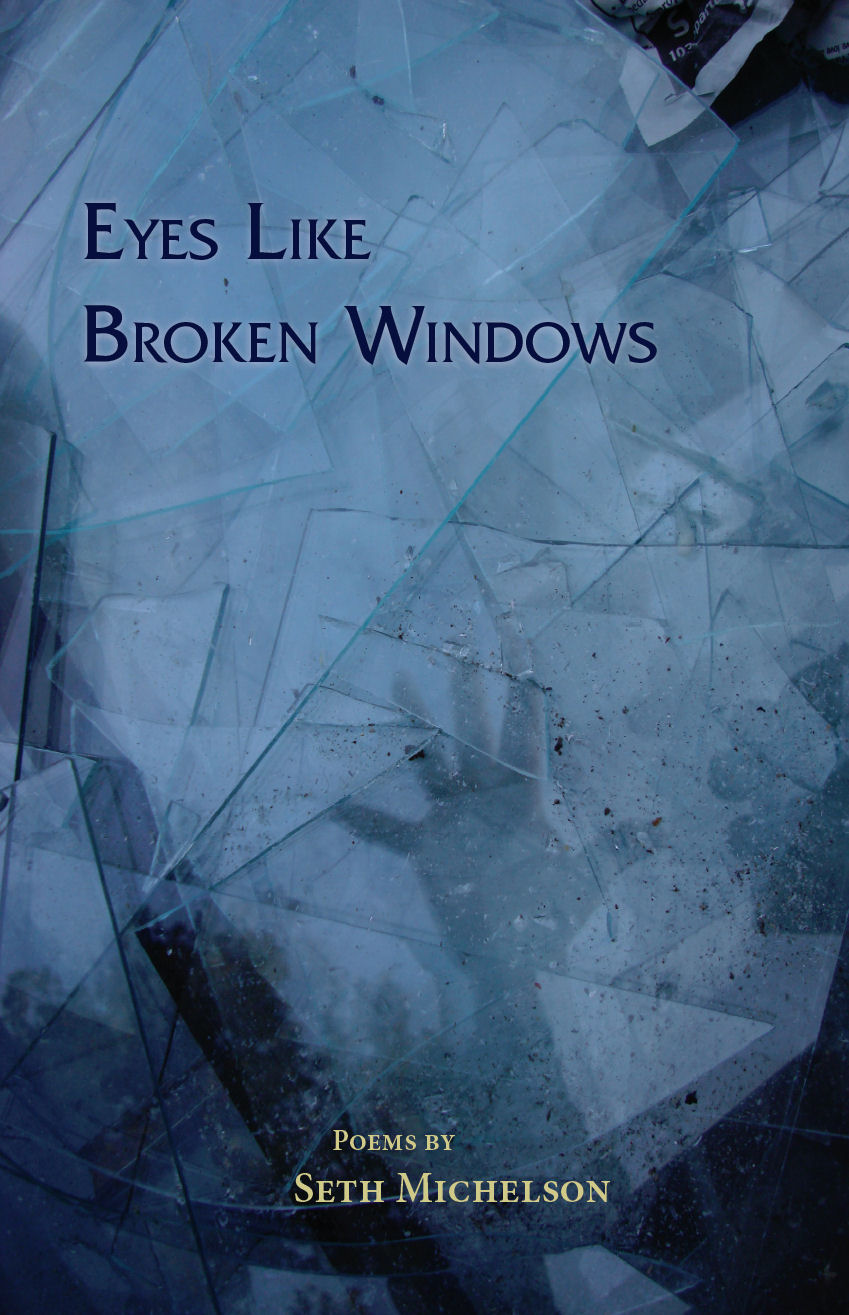

I’m happy today to present a conversation with Seth Michelson, author of poetry collection Eyes Like Broken Windows. And if you read to the end, you’ll see there’s an opportunity to get his book . . . for FREE!

I’m happy today to present a conversation with Seth Michelson, author of poetry collection Eyes Like Broken Windows. And if you read to the end, you’ll see there’s an opportunity to get his book . . . for FREE!

Welcome, Seth. Thank you for being here. Why don’t you tell us a little about yourself to get this started?

Well, thank you, Cliff. It’s a pleasure to be here to e-meet your readers (Hi, everyone!) and to converse with you.

But before talking about myself, I’d like to mention briefly what a fine writer you are, Cliff. Your newest book, What the Zhang Boys Know, is a great read. Its characters face disease, child loss, absent parents, and more, and through their travails, they teach us about endurance, about how to persist and to do so with compassion and joy. In other words, I admire your ability to render so artfully the anguish of interpersonal experience. It’s one of the reasons why I’m delighted to be here talking with you about writing.

As for me, I’ll say that I’m a poet, which simply means that I insatiably read and regularly write poems, and my newest book is Eyes Like Broken Windows. I’d like to add, too, that judging by public reactions (e.g. at readings, in book reviews, in fan emails), people really seem to be enjoying the book, for which I’m very grateful. I feel very fortunate that so many people are not only reading my book but taking the time from their busy lives to tell me about it.

I think one of the reasons why people are responding well to your book is that it’s an exciting book to read. It’s filled with a diversity of places, people, emotions, and poetic forms, ranging from sonnets to free verse. I’ve also noticed that you sometimes use both Spanish and English in there. Would you talk a little about that?

Sure, as a poet I’m very interested in the limits of language. In a complementary way, I’m interested, too, in challenging perfunctory social and cultural constraints. In my writing, I therefore like to identify and rethink my habits of being, including how I read, reflect, and write. Of course none of this emerges, or at least not in fully formed ways, when I sit down to begin to write. Rather, it emerges allusively, coyly, through a wisp of feeling, a captivating sound, a striking image glimpsed or imagined that jump-starts a new poem. From there, that tidbit grows into a poem through an exploratory process that creates itself through each act of writing. And for me, over the past few years (or longer…), this often includes a skittering along the vaporous border between English and Spanish within a poem, where I hope to hew alternative zones or pockets of experience, interlingual discursive spaces, within which a hybrid language emerges and asserts itself to inflect forms of being. In a sense, it’s one more way that a poet can inundate the reader with possibilities.

Could you give us an example of this?

Sure, in the central third of Eyes Like Broken Windows, I have a heroic crown of sonnets about a transnational, transhistorical network of experiences. As your readers know, a heroic crown of sonnets comprises fifteen sonnets sequentially linked into a circular cycle. I use that form to test the necessity of boundaries, both in life and in poetry, and I use the form, too, to weave together three narrative threads: my time living with a war criminal in Argentina from the genocide there (1976-83), my wife’s emigration from Argentina to the US during that era, and the story of a nineteen-year-old Argentine girl murdered by that war criminal. And as you noticed, the crown is bilingual at points, importing voices and vernaculars specific to moments in those interwoven stories. Nevertheless I think monolingual-English readers can understand it all contextually and via cognates. Plus I’ve included a glossary at the end of the book. And readers seem to really enjoy the crown. It’s an intrinsically fascinating form.

Tangentially, I’d like to mention, too, that the politics of bilingual poetry, and especially of the typography and formatting of bilingual books, fascinate me. And while I sympathize with positions against italicizing Spanish and adding glossaries, I do so in the crown because part of its intent is to offer a transcultural historiography: I hope for it to offer its U.S. monolingual-English audience something of importance about the period of the genocide in Argentine history, which is of course linked to U.S. history in particular and to postwar hemispheric and geo-politics in general. So my crown tries in small, poetic gestures to join those overlapping local and global discussions about how to live in the aftermath of extreme violence.

Interesting. Can I ask a quick question about nomenclature? I heard you refer to that period in Argentina as a “genocide,” which is new to me. I’d always heard it referred to as “The Dirty War.” Am I confusing two periods?

No, Cliff. You’re correct, and it’s a very good question. Both terms are used in reference to the dictatorship in Argentina from 1976-83. I prefer to use the term “genocide” as I find “Dirty War” a misnomer. There was no “war.” The military overthrew the democratic government, targeted civilians as enemies, and systematically murdered them. The symbolic civilian death toll from the period is 30,000. The military justified the torture and murder of these victims as being part of a necessary, if unusual, internal “war.” I, like many, see it instead as the fascistic slaughter of targeted categories of people, as genocide.

It’s a powerful subject, Seth. I noticed that you’ve also set some of your poetry about it to music, which I listened to on your website. Would you tell us about that?

Happily! I love music. I even fantasize about being a cellist [laughing]. So it was a very special experience for me to collaborate with the superb Chinese composer Zhou Tian. We set the first sonnet of the crown to operatic music for soprano, cello, and piano, and, as you mentioned, people can listen to it on my website, sethmichelson.com. Tian is a precociously masterful young composer, and our joint effort won First Prize at the 2009 ASCAP Art Songs Competition. More importantly, the piece has elicited powerful, positive responses from survivors of the Argentine genocide. It means a lot to me that it means a lot to them. These are people who’ve suffered severely—imprisonment, torture, the murder of friends and family—so it’s deeply gratifying and humbling to be able to help them with their pain in some small way.

I can imagine. In my experience, I’ve been very moved by hearing from readers of the Zhang Boys, for instance, about their life experiences in relation to the book. And speaking of readers, what are some books you’ve read recently and might recommend to us?

Well, on my way to the airport in Boston a couple of weeks ago for a flight home to LA, I picked up a copy of Don DeLillo’s novella The Body Artist, which is really idiosyncratic within his larger literary project. And I really enjoyed it (though a novella is too short for a five-hour flight; stupid oversight in book selection on my part! [laughing]).

I also am enamored with Catherine Malabou’s newest book in English, The New Wounded: From Neurosis to Brain Damage. Not only is it highly informative, but it’s iconoclastic in its analysis of neuroscience, brain trauma, and identity.

I’m also gearing up to teach poetry workshops starting next week in Los Angeles and then over the summer in New York, so I have teetering piles of books of poetry on my desk and floor, from which I’m distilling recommendations for my students, so feel free to check back with me about that (I can be reached easily through my website, about this or any matter).

Speaking of “other matters,” what are some of your hobbies? What do you enjoy doing besides reading and writing?

Well, I love to cook, so I spend a lot of time in the kitchen. I also always welcome recipes from others. So if you’re sitting on a good one, Cliff, then please consider sharing it with me. The same goes for all of you reading this. Send me recipes, please!

Do you ever write about food? Does cooking influence your poetry writing?

It does! In Eyes Like Broken Windows, for example, food appears often.

If you’ll permit it, here’s a related poem about those crucial instruments of eating, the teeth.

My Teeth In The Mirror

Smog-stained, coffee-stained, burnt

by digestive enzymes, they rim my mouth

like a harbor’s yellowed palings, stand

guard at the hideout’s door, gate-like

they open for the edible, divide like fences

my stench from New York’s. Plus how tenderly

they clasp nipples and lips in the dark!

O enameled, stalwart lovebuckles!

O speed bumps between my voice and the world!

Bear this corrosion until you’re withered

and your center’s deeply sore, then make me

believe in your cavities as metaphor:

That all the holes in a life

can be polished, filled with silver,

and, if rootless, dressed in layers of gold.

Great poem, Seth. Thank you. And thank you for this interview.

Thank you, Cliff. I’ve enjoyed this, and I hope that your readers do, too.

By way of thanks, I’d also like to make a special offer here to your readers: I’ll give away a free copy of my book (free!) to anyone who orders your book, What the Zhang Boys Know, before March 15. Take advantage, people! [Laughing…]

Thanks again, Cliff, and thanks to all of you out there for reading this.

Okay, readers, you heard the man. Anyone who orders a copy of my book, What the Zhang Boys Know, before March 15, either directly from me, or from Press 53, will ALSO get, absolutely free, a copy of Eyes Like Broken Windows. What a great deal. Thank you to Seth and Press 53 for their generosity.