Every year since 2001 I’ve seen at least one performance of A Christmas Carol at the American Shakespeare Center in Staunton, VA. The cast is always different—a different Scrooge, a different Ghost of Christmas Present, etc.—and the theater sometimes tweaks the adaptation so that regulars will have a fresh experience each year when they see this classic holiday play. (One memorable adaptation was the year they used a version set in Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia.)

This Christmas season, for example, instead of using a Narrator, which they have in years past, the narrative function was distributed among various actors, so that occasionally an actor would address the audience directly to convey the expository bits that the Narrator usually delivers. (The program notes suggest that this approach is closer to the original than the version we usually see.) Although there’s something I like about the function of the narrative voice (that’s the fiction writer in me, I assume), this distributed narration worked well for this production. That might be a function of this theater, which uses universal lighting and a lot of audience participation anyway. It’s not unusual for cast members to interact with audience members.

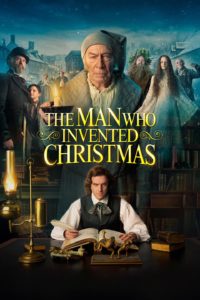

After the show, I intended to look at filmed versions of the play for a comparison, so I hopped on my Amazon Prime subscription. But instead of seeing A Christmas Carol, I stumbled on a movie called The Man Who Invented Christmas, a 2017 film directed by Bharat Nalluri that is about Charles Dickens and the writing of the short book that was later adapted into the familiar play. I doubt the historical accuracy of the story—Dickens is portrayed as nearly schizophrenic, at times cruel to his father and servants, aspects that do make the character more interesting—but what appeals to me about the film is its depiction of the writing process and the change that comes over the character of Dickens.

Dickens is shown as coming off a couple of flops, books that didn’t sell well and were reviewed badly. He’s in debt and under pressure to make some money quickly. His father shows up and needs money. His wife announces that she’s pregnant again, which adds to his worries. He hits upon the idea of writing a Christmas book, but then he can’t quite think of what to write. His publishers tell him no one cares about Christmas, which is a minor holiday in England at the time, so he is determined to self-publish the book (that is, the book he has not yet written). In his wanderings around the city, he catches glimpses of interesting characters—a miserly old man attending the funeral of his business partner, for example—and hears snippets of conversation that grab his attention. (“Are there no prisons? Are there no workhouses?”)

In his study at home, where he still hasn’t written anything, he speaks out loud to himself, trying out various names for the character of the miser he plans to use as the story’s centerpiece: Scrunge, Scratch, etc. His servant, a young Irish girl named Tara, overhears this and asks what the master is doing. Dickens explains that the character will come to him when he finds the right name. He tries a few more and then utters “Scrooge.” He realizes he’s got it right now, and in fact the character of Scrooge, played by Christopher Plummer, appears in the study.

Dickens then interacts with Scrooge, and to a lesser extent the other characters as well. He’s getting to know them, their motivations and their personalities. Scrooge even accompanies Dickens when he goes around London, which allows the author to learn even more about his character. Dickens has written most of the book at this point, but doesn’t know how to end it, so he’s planning to be done with Scrooge, who begs to be allowed to live, and this is the epiphany that allows Dickens to complete the story. (There’s also a nice scene where Tara, the maid, begs for Dickens to save the life of Tiny Tim, who in an earlier chapter, appears doomed.) The process also allows Dickens to realize something about himself and to make a change for the better, which is the real point of the story.

I recently taught a seminar I titled “The Care and Feeding of Compelling Characters” in which I discussed the need to know as much about your characters as possible as a way of understanding how they would behave in any given situation. To accomplish this, I recommended completing a Character Questionnaire that identifies both physical and personality traits (in excruciating detail). But the next time I give this particular seminar (at the High Road Festival of Poetry and Short Fiction in March), I plan to make some adjustments. It isn’t enough, maybe, to know your character on paper. Perhaps you need to conjure these characters and converse with them, argue with them, travel with them. Only then will you really know what drives them and what they want.